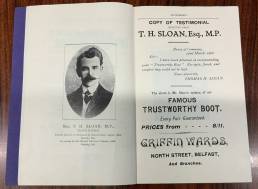

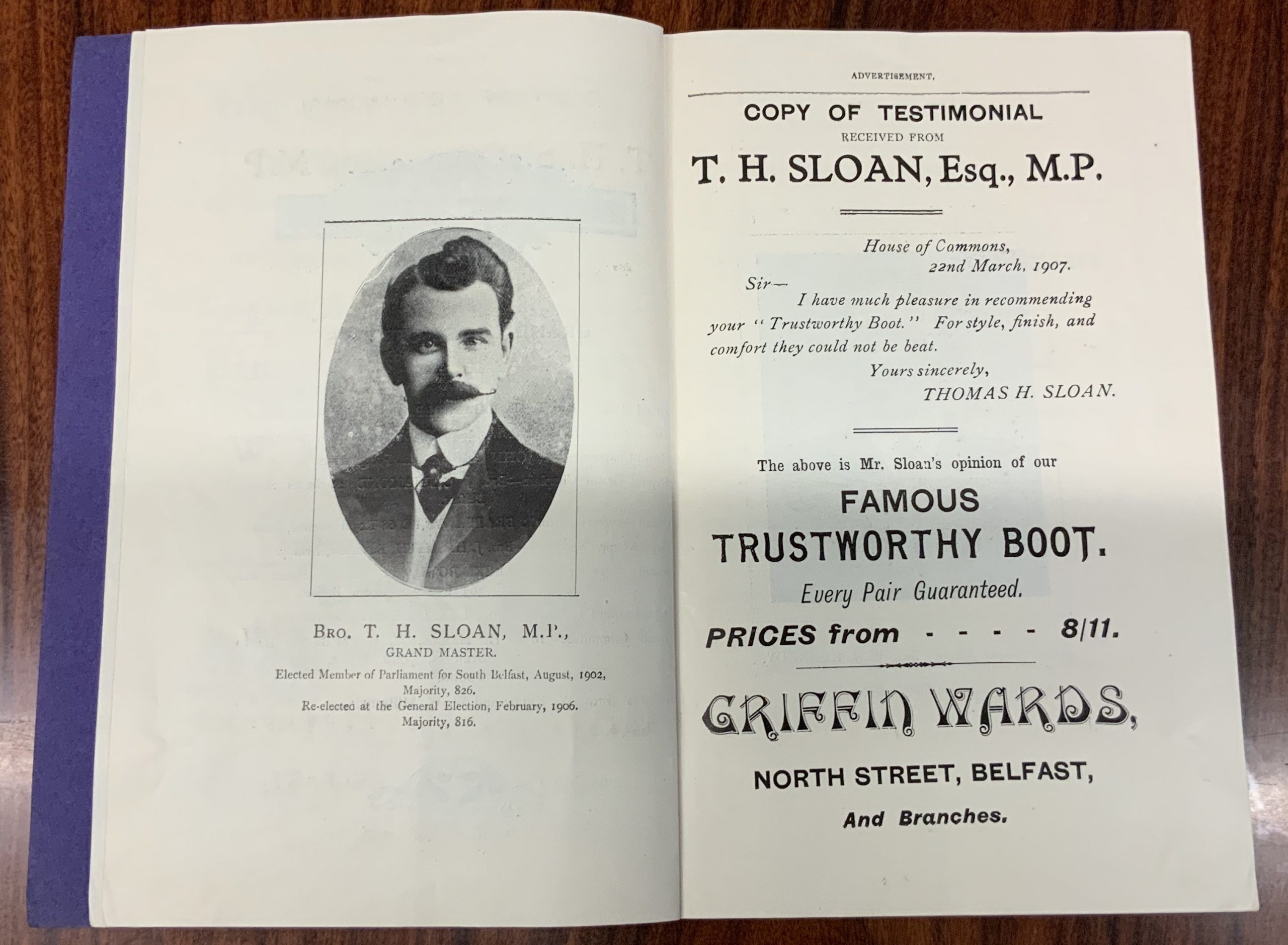

An advert for men’s boots endorsed by Tom Sloan MP in one of the first celebrity endorsements in Ireland. The advert came in the wake of a political fashion scandal where his critics used Sloan’s fashion as a means of questioning his working-class credentials.

Description

Description

Today we are bombarded with advertising, with social media developing secret algorithms to specifically target us. From television adverts to the billboards we drive past to social media influencers product placement, media adverts and offers are a part of everyday life.

Since print was invented and the first news sheets rolled off the presses, businesses have used them to sell their wares directly to readers. Over the years this has become sophisticated with the use of pictures and other tools. The first and many would argue one of the biggest innovations in marketing and advertising in the Twentieth Century was the celebrity endorsement.

Today our buying habits are often dictated by the television, film or sports stars we follow. The cost of these endorsements is eye-watering with David Beckham signing a $160 million lifetime deal with Adidas, Tiger Woods $100 million to be the face of Nike or Taylor Swift becoming a brand ambassador for Diet Coke in a deal reportedly worth $26 million. The price paid gives a good indication of exactly how valuable these companies place on a celebrity endorsing them.

History of Celebrity Endorsement

While the history of celebrity endorsement of products dates back to the 1760s it really only began properly in the early 1900s. Josiah Wedgwood, the founder of the Wedgwood brand of pottery and chinaware, was called the father of the modern brand when he used royal endorsements and other marketing devices to create an aura around the name of his company which gave the brand value far beyond the attributes of the product itself. The use of ‘By Appointment to Her Majesty the Queen” is still a popular way of adding exclusivity or tradition to a brand.

Between 1875 and 1900, the next development was the trade card, either handed along with the product to the customer or inserted in the packaging itself, it used an early crude form of a celebrity endorsing. The card had a picture of the celebrity and a product description but had no quote or a direct testimonial by the celebrity.

Between 1875 and 1900, the next development was the trade card, either handed along with the product to the customer or inserted in the packaging itself, it used an early crude form of a celebrity endorsing. The card had a picture of the celebrity and a product description but had no quote or a direct testimonial by the celebrity.

The United States led the world in the new form of advertising celebrity endorsement. Author Mark Twain (1835-1910), who wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn had a huge readership – think J K Rowling and you get the idea! He pioneered the endorsement campaigns of three brands concurrently: Great Mark Cigars, Mark Twain Cigars and Mark Twain flour! He appeared in an ad, and endorsed, Fountain Pens cashing in on his fame as an author.

In Britain and Ireland, it took a while for this new approach to catch on with the first celebrity endorsement by Lillie Langtry. Langtry (born Emilie Charlotte Le Breton; 1853-1929) was a British music hall singer and actress famous for her many stage productions including ‘She Stoops to Conquer’, ‘The Lady of Lyons’ and ‘As You Like It’. She was also known for her scandalous relationships with the nobility, including the Prince of Wales, Albert Edward, the Earl of Shrewsbury and Prince Louis of Battenberg.

Langtry used her high public profile to endorse commercial products such as cosmetics and soap, becoming one of the first examples of ‘celebrity endorsement’. Her famous ivory complexion brought her income as the first woman to endorse a commercial product, advertising Pears Soap. Her fee was reportedly matched to her weight so she was paid ‘pound for pound’.

It is therefore interesting that by 1907 after only five years in the public eye as an MP for a provincial seat that Thomas Sloan is the face of an advertising campaign. A local shoe and boot maker with a small chain of stores wrote to Sloan in 1906 and supplied products to him in exchange for his ‘celebrity endorsement’. It was a big step for both shoemaker and the young MP. For the businessman it could have ruined his trade in a divided city like Belfast, and few have risked allowing an Irish politician or any persuasion to become a face of their brand since. For Sloan in an age when Parliament was still the preserve of the landed and wealthy taking free products in exchange for his endorsement would have been a radical move.

Sloan as a Fashion Icon

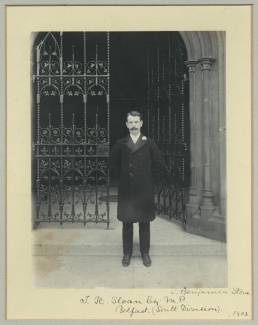

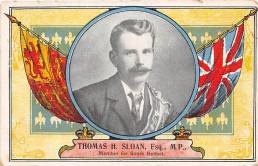

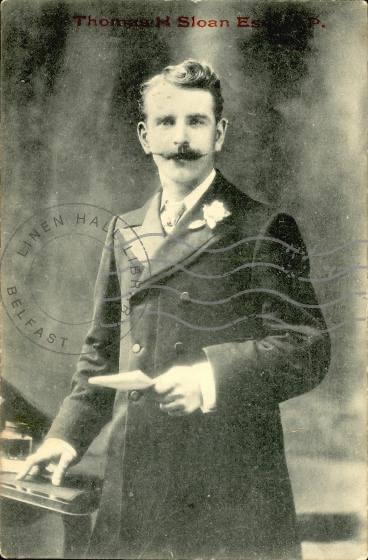

Given our modern perception of the fashion icon, it is hard to apply it to an Edwardian politician from a provincial capital like Belfast. But Sloan was not only known for his dress sense but like many, figures in the media he was both attacked and praised for it. He earns the title because he was certainly the first public figure in Belfast if not Ireland to become the face of a fashion brand. Being chosen and then agreeing to endorse the product tells us many things, such as the celebrity status relatively speaking of Sloan, and something of the integrity and honesty that the advertiser felt came with his name. It was also testimony to the fact that Sloan was seen as something of a fashion icon, a dandy whose fashion sense was known to have got him into trouble even with his own supporters.

Sloan was a small man, but cut a dash, much in contrast to the great drab ageing politicians around him. His shock of black hair and manicured moustache contrasted to a fair complexion. Contemporaries spoke of sparkling eyes which held an audience in thrall. Despite his  humble beginnings he worked hard and was always well presented in well-tailored suits, often sporting a flower or pocket square.

humble beginnings he worked hard and was always well presented in well-tailored suits, often sporting a flower or pocket square.

His keen fashion sense no doubt developed when in London, and it was even used by his critics to question whether he was still in touch with his working-class roots and electorate. It would appear that in the winter of 1905 or early in 1906 he appeared in Belfast at meetings and events sporting a fine Ulster coat with the collar and lapels trimmed in fur. A hostile media seized on the image and drew a comparison with the less stylish and more threadbare outfits of his followers. A cartoon in the Belfast Evening Telegraph (14 July 1906) shows Sloan wearing a fur-collared coat labelled ‘Conciliation’ with a discarded ‘No pope’ hat lying on the floor.

It is an interesting insight into the minds of his enemies and supporters, which saw a direct link between dress and beliefs. At a time when dress codes had much more significance audiences often judged speakers as much by their presentation than their words. For a man who had carved a political career out of criticising ‘big house unionism’ and the ‘fur coat’ brigade, it was perhaps a gaffe to follow suit in styles. What Sloan had to do to fit into political circles in London often worked in reverse in Belfast. The workingmen, and women of Belfast were often a hard audience, and hated airs and graces especially from those they remembered being brought up in their own streets and schools. Even interviewing Sloan’s supporters in the 1960s J W Boyle cites three interviews where the witnesses expressed distress and ‘some dismay that within a few years he had become quite a dandy in matters of dress’

However the Great Coat Scandal of 1906 while doubtless costing him votes, in the long run, did offer the opportunity for his celebrity endorsement. It was no doubt on the back of the publicity, and the acknowledgement that he was a man of taste and style that his endorsement for footwear became desirable. It was also a safer bet for Sloan, since his choice of overcoats had not been a popular one! It was a very enterprising businessman who saw a local MP as a celebrity for the first time. Perhaps the fashion debate had grabbed his attention or the fact that he knew Sloan had a huge following in Belfast which could translate into influence over everyday purchases.

One wit has suggested that given the parading and marching engaged in that the popular leader of Belfast Orangeism was an obvious choice to endorse a good walking boot! More likely was the idea that Sloan had a reputation for honesty and integrity, for telling it as he saw it. His ‘one of us’ credentials meant that he was a role model for many, is this small kid from Sailortown could be taking up the cause of Belfast in the Imperial Parliament of the British Empire then there was no limit to what a hard-working Belfast man could achieve.

Many wanted to follow him and follow in his footsteps, a good advertiser who was a century ahead of his time realised the value of that sort of endorsement.

Accession Number

MIC1907/p1

Copyright/Ownership

Independent Loyal Orange Institution

Location

McNeillstown Museum and Interpretative Centre